TWO NEW EXHIBITIONS FEATURE MIZER WORKS THROUGH LATE AUGUST

Coming off of the heels of the successful #Rawhide exhibit at Venus Over Manhattan in New York, Bob Mizer's works have now gone up on the walls of...

3 min read

Bob Mizer Foundation : Updated on April 6, 2024

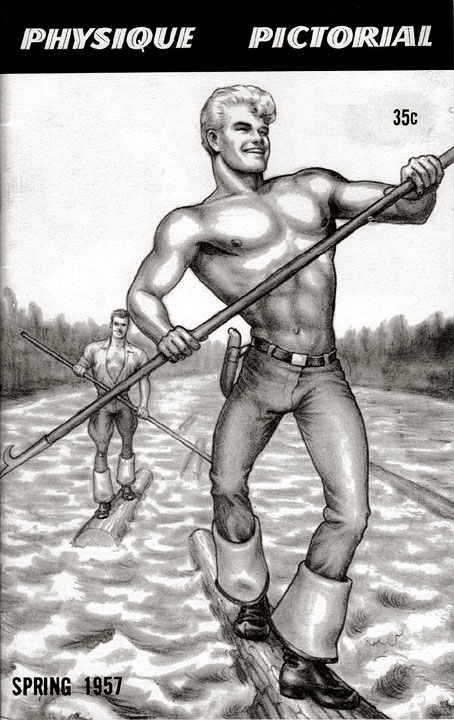

They were truly everyman – mostly unknown, private figures whose lives were turned upside down with the opening of a package. Maybe it was a male physique magazine. Or a series of photographs or slides. Whatever the offending materials, their secret desires were suddenly illuminated, stripped nearly as bare as the men who graced the pages of their beloved magazines.

The government’s crackdown on those who violated obscenity laws that made it illegal to send erotic and receive ‘obscene’ materials through the U.S. Postal Service reached its zenith during the Red Scare of the 1950s. Most of these private men became infamous overnight after enduring the feelings of shock, humiliation and despair that accompany an arrest and conviction of such a nature. One of the most highly visible cases of the decade, however, ended the career of a great scholar and writer who had secured a place among the luminaries of the literary world. His lover was the up-and-coming novelist, Truman Capote, who skyrocketed to fame with the publication of his novella, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” in 1958, and would later earn critical acclaim for his true crime novel, "In Cold Blood."

Newton Arvin, already an esteemed academic and literary critic when he met the young Capote in 1946, was a professor of English at Smith College in Massachusetts, having already penned biographies of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman when Capote was a mere child growing up in New Orleans. Arvin was nearly 25 years Capote’s senior when the two met in the summer, and he seemed to be the unlikeliest candidate for the handsome young author’s affections. According to Capote biographer Gerald Clarke, Arvin was “bald, bespectacled, slight, shy anemic, a victim of depression, vertigo, and a score of other psychological ailments – in short … the popular image of the mousy college professor.”

Newton Arvin, already an esteemed academic and literary critic when he met the young Capote in 1946, was a professor of English at Smith College in Massachusetts, having already penned biographies of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman when Capote was a mere child growing up in New Orleans. Arvin was nearly 25 years Capote’s senior when the two met in the summer, and he seemed to be the unlikeliest candidate for the handsome young author’s affections. According to Capote biographer Gerald Clarke, Arvin was “bald, bespectacled, slight, shy anemic, a victim of depression, vertigo, and a score of other psychological ailments – in short … the popular image of the mousy college professor.”

But Capote was captivated by Arvin’s mind and his scholarly pursuits. The whirlwind courtship between the two men has been well documented through an exchange of letters throughout the late 1940s. Arvin, for his part, was quick to recognize Capote’s immense potential and talent as a wordsmith.

“Dear Truman … it would not be possible for me to cherish you more tenderly … than I already do,” Arvin gushed in a 1947 letter to the budding author, “but if it were possible, your stories would have that effect.”

Although his joy at having met Truman and finally embracing his identity as a gay man meant that he was “euphoric and chipper,” Arvin’s psychological demons loomed large. He suffered from chronic depression, and wrote of his own torment in the years before he met Truman Capote. In the years before they met, Arvin, who married one of his own students in 1932 and watched his marriage dissolve into divorce eight years later, had tried to take his own life three times. A suicidal tendency would rear its hideous head years later, after his arrest.

Arvin and Capote ended their romantic relationship in late 1949, only a year before Arvin wrote his famous biography of “Moby Dick” author Herman Melville and two years before he received the coveted National Book Award for the volume. The two did remain close friends throughout the 1950s, when Capote’s star began to shine brighter and Arvin’s began a slow burn.

As the 1950s progressed, Arvin’s sexual tastes became more risqué and threatened to endanger the reputation he had worked so hard to cultivate. In the late 1950s, Arvin began to exchange nude photos and stories through the mail. It didn’t take long for his illegal activities to be unearthed. In September 1960, the U.S. Postal Service and the police, acting on a tip from the raid of a male physique magazine publisher, executed a raid on Arvin’s home in Northampton and seized thousands of ‘obscene’ stories and still images.

As the 1950s progressed, Arvin’s sexual tastes became more risqué and threatened to endanger the reputation he had worked so hard to cultivate. In the late 1950s, Arvin began to exchange nude photos and stories through the mail. It didn’t take long for his illegal activities to be unearthed. In September 1960, the U.S. Postal Service and the police, acting on a tip from the raid of a male physique magazine publisher, executed a raid on Arvin’s home in Northampton and seized thousands of ‘obscene’ stories and still images.

Obscene materials? It was a devastating discovery for a man who even detested the use of profane language. Still, officially, authorities charged Arvin with being a “lewd and lascivious person in speech and behavior.”

According to Clarke, Arvin referred to the day of his arrest as “the day of the avalanche,” and left his diary blank for the remainder of 1960. His mental health issues temporarily spared him from prison – he suffered a nervous breakdown as he awaited trial and was instead was admitted to the Northampton State Hospital. Later, at trial, Arvin pleaded guilty to the charges against him and paid a $1,200 fine.

Capote, who was living in Europe in 1960, wrote an impassioned letter of support to Arvin assuring the disgraced scholar that “all your friends are with you, of that you can be sure.” Even Arvin’s now-former employer, Smith College, kept Arvin’s name on the English faculty list and paid him a small stipend.

Terror-stricken and near-suicidal, Arvin’s own cowardice wasn’t his downfall but his saving grace. In exchange for a one-year suspended sentence, Arvin became an informer for the police, giving officials the names of 15 men he knew sent and received pornographic materials through the mail, including two of his own faculty colleagues.

“He panicked and ratted, poor bastard,” Clarke quoted one of Arvin’s friends as saying in his biography of Capote. “He must have been in total terror.”

There is no indication that Arvin ever expressed remorse for his betrayal of his friends in the short time he had left on earth. The man who had earned renown, both as a gifted academic and as the lover of one of the 20th century’s greatest literary voices, died in the spring of 1963.

Arvin’s case proved that, from the private figure to the public scholar, no gay men in the 1950s and early 1960s were safe from law enforcement and government officials who targeted them in a misguided attempt to uphold their community’s moral virtue. Additionally, Arvin’s betrayal of other consumers of male erotica added a disturbing realization that, where one’s sexuality was concerned, one never knew whom to trust with one’s secrets.

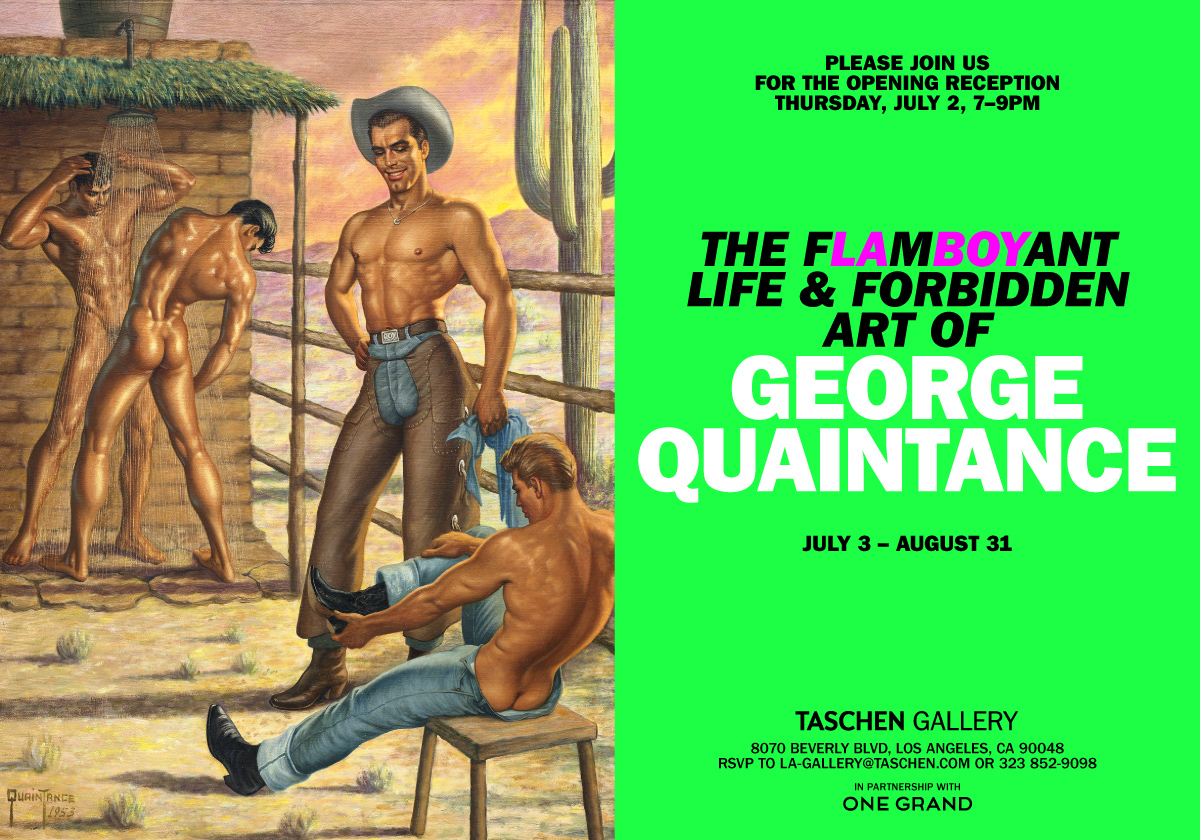

Coming off of the heels of the successful #Rawhide exhibit at Venus Over Manhattan in New York, Bob Mizer's works have now gone up on the walls of...

In the early 1960s, just a few years before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that nudity in art was not obscene, one artist’s career began with a literal...

The editors of most magazines welcome letters to the editor, allowing readers to praise, question or criticize editorial decisions made by the...

Author’s note: This is the fourth and final part of a four-part series designed to introduce the novice to photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer. Part...