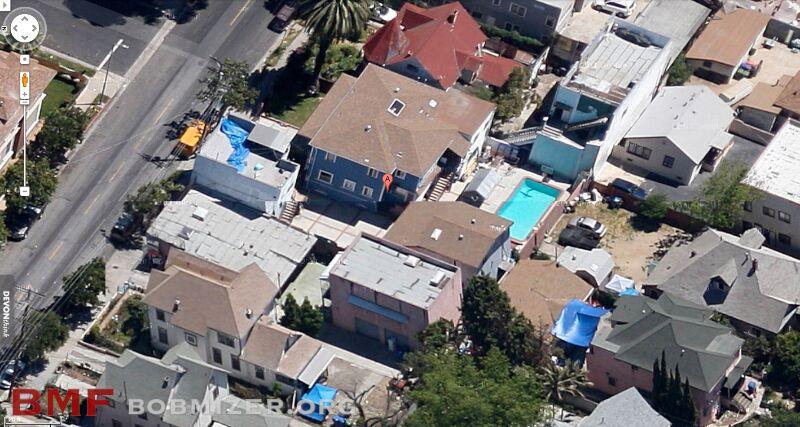

Mizer compound at center of photographer's empire

When the neighbors watched Delia Mizer and her precocious 5-year-old son Bob move into the Victorian house at 1834 W. 11th St. in Los Angeles in...

4 min read

Bob Mizer Foundation : Updated on April 5, 2024

Author’s note: This is the third part of a four-part series designed to introduce the novice to photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer. We will post a new installment to this series on our blog each week for the next month. Part III will explore Mizer’s life from 1968, the year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that nudity in art wasn’t obscene, to his death in 1992.

A little more than a decade after Beat poet Allen Ginsburg’s poem “Howl” won a major victory when it was determined to have artistic merit, Bob Mizer claimed his own victory when the U.S. Supreme Court legalized sexual nudity in art in April 1968.

Mizer’s empire continued to grow in the years leading up to the ruling. In Los Angeles, his compound specifically grew as he purchased land (and with it, structures) surrounding the house in which he grew up. Now, in the waning years of the 1960s, Mizer’s domain included an office building, pool area, guest housing and even a faux woodsy outdoor set where many of his movies and still images were shot. Now free of the disapproving eyes of his mother, Delia, Mizer welcomed models into the compound, where they came and went freely, some living on the grounds for a few days, some for weeks, months or even years. A veritable zoo of animals now populated the Mizer compound, too, scattered throughout buildings and yards, where they roamed and were taken care of by Mizer’s models.

Mizer’s empire continued to grow in the years leading up to the ruling. In Los Angeles, his compound specifically grew as he purchased land (and with it, structures) surrounding the house in which he grew up. Now, in the waning years of the 1960s, Mizer’s domain included an office building, pool area, guest housing and even a faux woodsy outdoor set where many of his movies and still images were shot. Now free of the disapproving eyes of his mother, Delia, Mizer welcomed models into the compound, where they came and went freely, some living on the grounds for a few days, some for weeks, months or even years. A veritable zoo of animals now populated the Mizer compound, too, scattered throughout buildings and yards, where they roamed and were taken care of by Mizer’s models.

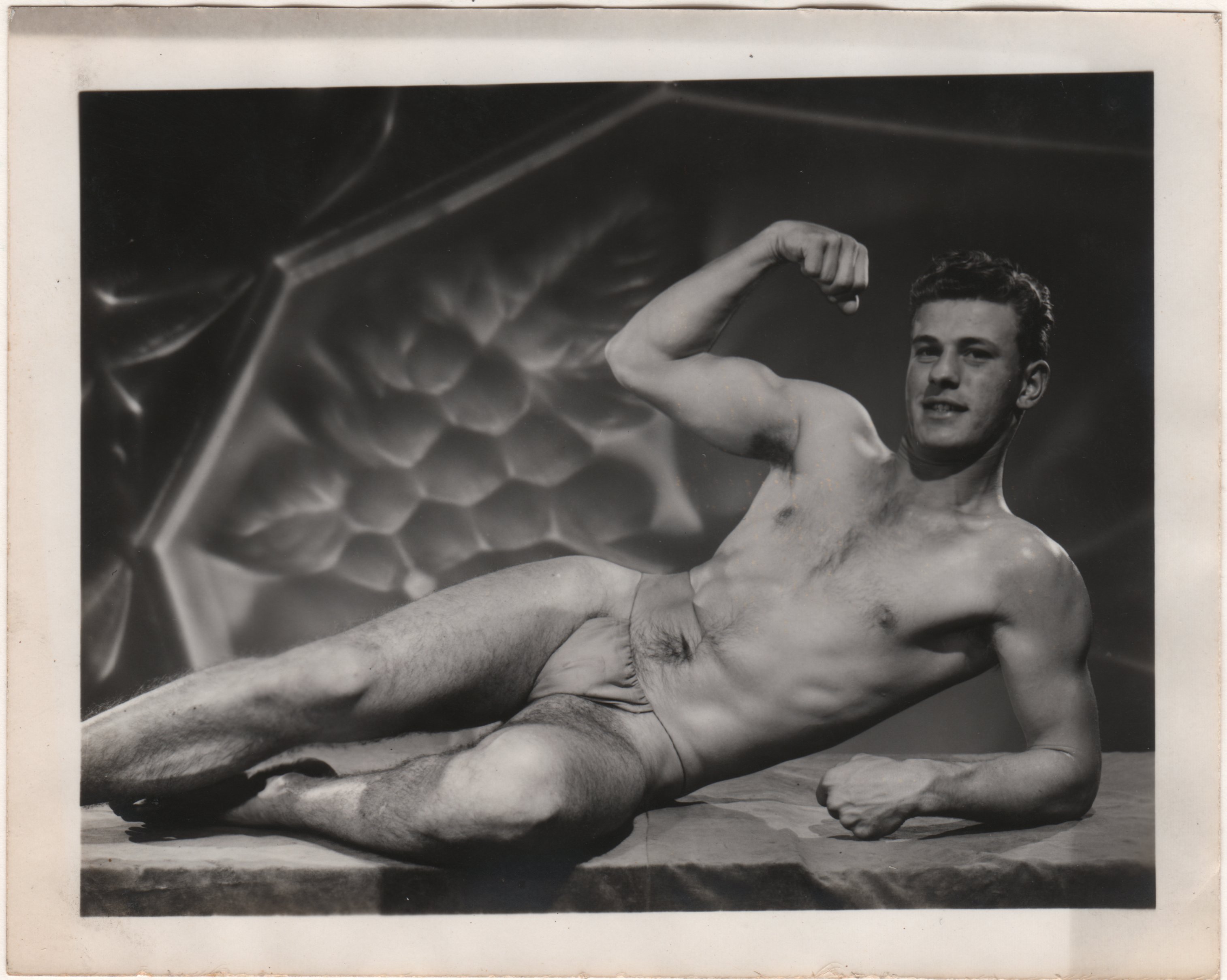

And so, with the growing popularity of “Physique Pictorial” and Mizer’s color films detailing the antics of scantily clad sailors, Greek gods, nymphs and cowboys, life seemed good for the artist. But there was still one restriction that hindered his work – the illegality of full-frontal nudity in art. Mizer kept his models clad in snugly-fit posing straps in order to protect himself and his art, too.

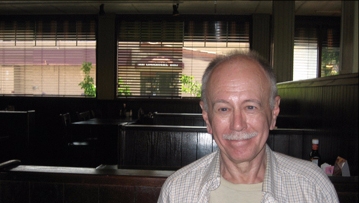

“All of that changed with the court’s 1968 ruling. After that, the fig leaf fell,” says Den Bell, founder and president of The Bob Mizer Foundation. “Mizer began once again freely photographing full-frontal nudity at his AMG studio, something he had not done since the mid 1940s. He had tentatively explored it a few years earlier in films that documented nudist camps, places like Ramona Ranch, Hemet and Homeland. These films really set the stage for the golden age of pornography in the early and mid-1970s.”

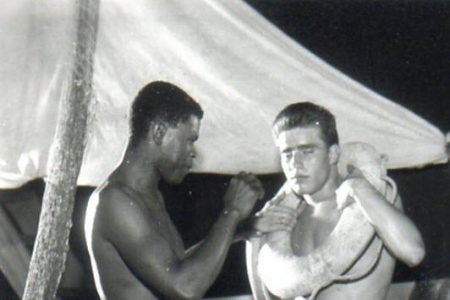

However, with the court’s ruling and nudity making its way into the pages of “Physique Pictorial” also came a change in the types of models photographed by Mizer. The models of his 1950s and early 1960s works were beefy, boy-next-door bodybuilders, almost exclusively Caucasian. Mizer began shooting more models of color to appease the diverse tastes of his audience.

More notable, though, were the types of models he shot. The angel-faced, traditionally handsome models of the 1950s gave way to more rough-trade types – criminals, porn stars, hustlers, junkies festooned with tattoos, chipped teeth and matted hair, flexing their muscles and sneering almost angrily into the camera. Mizer brought their personalities to life through his model guide, a small visual, biographical glimpse into their world. Tiny symbols that ran alongside each individual model’s photo shoots denoted a certain personality trait – affable, conceited, hardworking, lazy, religious, quarrelsome. Every symbol had a meaning, and in later issues of “Physique Pictorial,” it seemed that more and more models were linked to a criminal past or some nefarious activities.

Even as Mizer’s denizens became more morally questionable, at least by 1970s standards, his star continued to blossom.

Even as Mizer’s denizens became more morally questionable, at least by 1970s standards, his star continued to blossom.

“Only a year before the Supreme Court’s nudity ruling, Mizer shot Joe Dallesandro in the nude in the Athletic Model Guild studio, which was very bold and very like him,” Bell notes. “Of course, Dallesandro was on his way to becoming a star in Andy Warhol’s pop art circles.”

As the 1970s progressed, more outsiders took notice of the AMG empire. A documentary, Inside AMG, was shot at the AMG studio and released in 1973; only two years later, Mizer would shoot the bodybuilder and actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who would go on to become the governor of California in 2003.

“At that point, Mizer, it seemed, had finally crossed over from a niche market into a more mainstream audience,” Bell says.

As the 1980s dawned, Mizer wisely listened to the advice of his friend and contemporary, David Hurles of Old Reliable Studios, who urged him to experiment with new video technologies. Mizer began to focus more heavily on shooting close to home and recording complete two and three hour "session videos" at that point, while balancing his work with “Physique Pictorial.”

The bursts of color in his films and images were unquestionably Mizer. Here, scraggly-haired lads wrestled with one another against colorful backdrops boasting royal blue skies and purple mountains. Models appeared to soar through the air in leather restraints, suspended in time by Mizer’s lens. The addition of color to his works, shot throughout various locations in and outside of his complex, conveyed a playful eroticism – and almost always nude.

At least one of Mizer’s models, Ed Taylor, who had previously appeared in the AMG film “Slave Ship,” lived in the compound and cared for Mizer, who was plagued by health problems in his later years. Though still very much interested in sex, his models were now de facto family members who looked after Mizer, their patriarch – after all, Mizer had taken them in, given them a place to live, taught them responsibility and the importance of good health. It was the least they could do.

Mizer’s journal entries in the last few years of his life reveal a struggle with gout, an affliction of excess. In medieval times, it was believed only to strike the affluent who enjoyed fatty meats and alcohol. In a way, it seemed a fitting ailment for Mizer, who enjoyed all of the hedonism life had to offer.

Mizer’s journal entries in the last few years of his life reveal a struggle with gout, an affliction of excess. In medieval times, it was believed only to strike the affluent who enjoyed fatty meats and alcohol. In a way, it seemed a fitting ailment for Mizer, who enjoyed all of the hedonism life had to offer.

In the spring of 1992, Mizer shot his last model. His failing health had made keeping up with the rigors of regular work an exhausting task. He died of cardiac arrest on the evening of May 12, 1992, leaving behind over two million still images and thousands of films. Only one month later, the heir to Mizer’s estate – his brother, Joe – died, leaving everything to Wayne Stanley, who lived in the compound himself.

In mid- to late 1992, as broken props, stained mattresses, collapsed columns and antique equipment were unceremoniously hauled to dumpsters and discarded, and boxes of photographic material were sealed away in storage lockers, it seemed as if that would be the end of Bob Mizer’s story. But the last-ditch effort to preserve the Mizer name and his enormous body of work was still on the horizon. Soon, a new generation of artists would learn the story of Bob Mizer.

Next week -- Part IV will chronicle the founding of The Bob Mizer Foundation and examine Mizer's lasting legacy to the art world.

When the neighbors watched Delia Mizer and her precocious 5-year-old son Bob move into the Victorian house at 1834 W. 11th St. in Los Angeles in...

Author’s note: This is the fourth and final part of a four-part series designed to introduce the novice to photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer. Part...

Bob Mizer counted many people among his friends and acquaintances. His compound -- especially in the later years of his career -- was always buzzing...

3 min read

When I first saw Bob Mizer’s late period color work, it looked to me like the work of an outsider – someone who created great art unintentionally,...