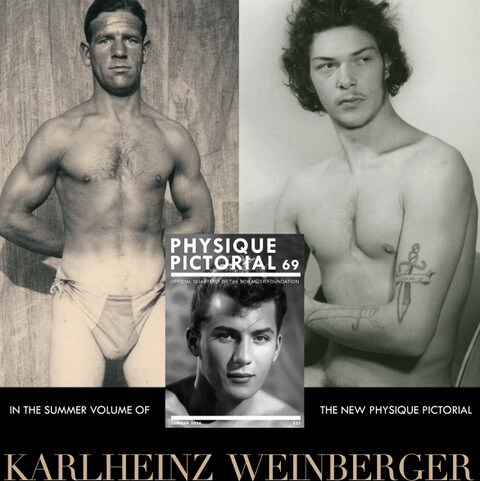

Exploring Swiss Counterculture: Karlheinz Weinberger

Step into the mesmerizing realm of Swiss counterculture as seen through the visionary eyes of photographer Karlheinz Weinberger. Weinberger's lens...

2 min read

Bob Mizer Foundation : Updated on April 5, 2024

Although most followers of media law are familiar with the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1968 ruling in Ginsburg v. New York that nudity in art could not be ruled obscene, one court case in the late 1960s also had the attention of male physique photographers, including Bob Mizer.

The year before the court announced its ruling, U.S. district attorneys, postal service inspectors and U.S. Marshalls swarmed a publishing plant in Minneapolis, arresting owners Conrad Germain and Lloyd Spinar. The two men were charged in federal court in Minneapolis with 29 counts of producing and distributing obscene materials. Germain and Spinar owned a company called Directory Services Inc. (DSI), a Minneapolis-based company that produced publications geared toward gay men. Titles included Tiger, Butch and Greyhuff Review. Like Mizer, the men also kept a collection of photo slides of male models, many of which they sold to clients. Each man faced the possibility of 145 years in prison and nearly $150,000 in fines, if convicted.

The year before the court announced its ruling, U.S. district attorneys, postal service inspectors and U.S. Marshalls swarmed a publishing plant in Minneapolis, arresting owners Conrad Germain and Lloyd Spinar. The two men were charged in federal court in Minneapolis with 29 counts of producing and distributing obscene materials. Germain and Spinar owned a company called Directory Services Inc. (DSI), a Minneapolis-based company that produced publications geared toward gay men. Titles included Tiger, Butch and Greyhuff Review. Like Mizer, the men also kept a collection of photo slides of male models, many of which they sold to clients. Each man faced the possibility of 145 years in prison and nearly $150,000 in fines, if convicted.

“Such punishments were commonplace among those producers of physique magazines and movies who were unfortunate enough to be caught by law enforcement,” says Dennis Bell, founder and president of the Bob Mizer Foundation. “Law enforcement monitored artists like Bob Mizer very closely, and Mizer himself lived in constant fear of being fined, imprisoned or worse.”

Germain and Spinar enlisted the assistance of defense attorney Ron Meshbesher, who used what would later be referred to as a “community standards” defense. He argued that the availability of nude female images “meant that it was reasonable for there to be nude male images … available to the public,” according to the University of Minnesota Libraries, which houses several boxes of evidence items entered into the trial.

Germain and Spinar enlisted the assistance of defense attorney Ron Meshbesher, who used what would later be referred to as a “community standards” defense. He argued that the availability of nude female images “meant that it was reasonable for there to be nude male images … available to the public,” according to the University of Minnesota Libraries, which houses several boxes of evidence items entered into the trial.

“(Meshbesher) even went so far as to hire a private investigator to prove that there was demand for nude images of both sexes, and that female nudes were more readily available and easily accessible, especially in publications like Playboy,” Bell says.

Meshbesher also conducted a survey of purchasers of nude male publications, movies and slides. The results of the survey confirmed what we already know today – that it wasn’t just men who craved these images. Women were frequent consumers of them as well.

“That was probably the most surprising bit of information to emerge from Meshbesher’s defense,” Bell notes.

“That was probably the most surprising bit of information to emerge from Meshbesher’s defense,” Bell notes.

An impressive group of witnesses for the defense made their way to the stand to testify on DSI’s behalf, including a liberal clergyman, a sociologist, a physician, and even Wardell B. Pomeroy, a former researcher with the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, which studies issues related to sex, gender and reproduction.

The case became so widely known that it made the cover of a new, fledgling magazine called The Advocate – now regarded as one of the seminal outlets for news about the LGBT community. News of the DSI trial appeared in Volume I, Issue I of the magazine.

Meshbesher’s tactics worked. The trial, which lasted only two weeks, resulted in a dismissal of all charges. Perhaps even more importantly, however, the postal system could now be used to distribute sexually explicit materials.

Judge Earl Larson, in his ruling, noted that “the materials have no appeal to the prurient interests of the intended recipient deviant group; do not exceed the limits of candor tolerated by the contemporary national community; and are not utterly without redeeming social value.”

Judge Earl Larson, in his ruling, noted that “the materials have no appeal to the prurient interests of the intended recipient deviant group; do not exceed the limits of candor tolerated by the contemporary national community; and are not utterly without redeeming social value.”

Larson’s ruling was a relief to male physique photographers, publishers and consumers alike. Only a year after the ruling, the “the artistic, bodybuilding, and classical alibis that had been used to justify male nudity fell away. Within a year publications appeared with cover photos of naked men in bed, the sexual connotations no longer even thinly disguised,” according to Prof. David Johnson of the University of South Florida, writing for The Journal of Social History.

In the years that followed, more publications began printing, and magazines and films dropped the pretense of existing only to promote health. Now, consumers could enjoy such offerings for their pure sexuality. DSI’s victory in court meant that the careers of artists such as Bob Mizer would soon go through a renaissance.

In the coming weeks, The Bob Mizer Foundation’s blog will explore other court cases like this one in more depth to illustrate the long history and fight for artistic freedom of expression.

Step into the mesmerizing realm of Swiss counterculture as seen through the visionary eyes of photographer Karlheinz Weinberger. Weinberger's lens...

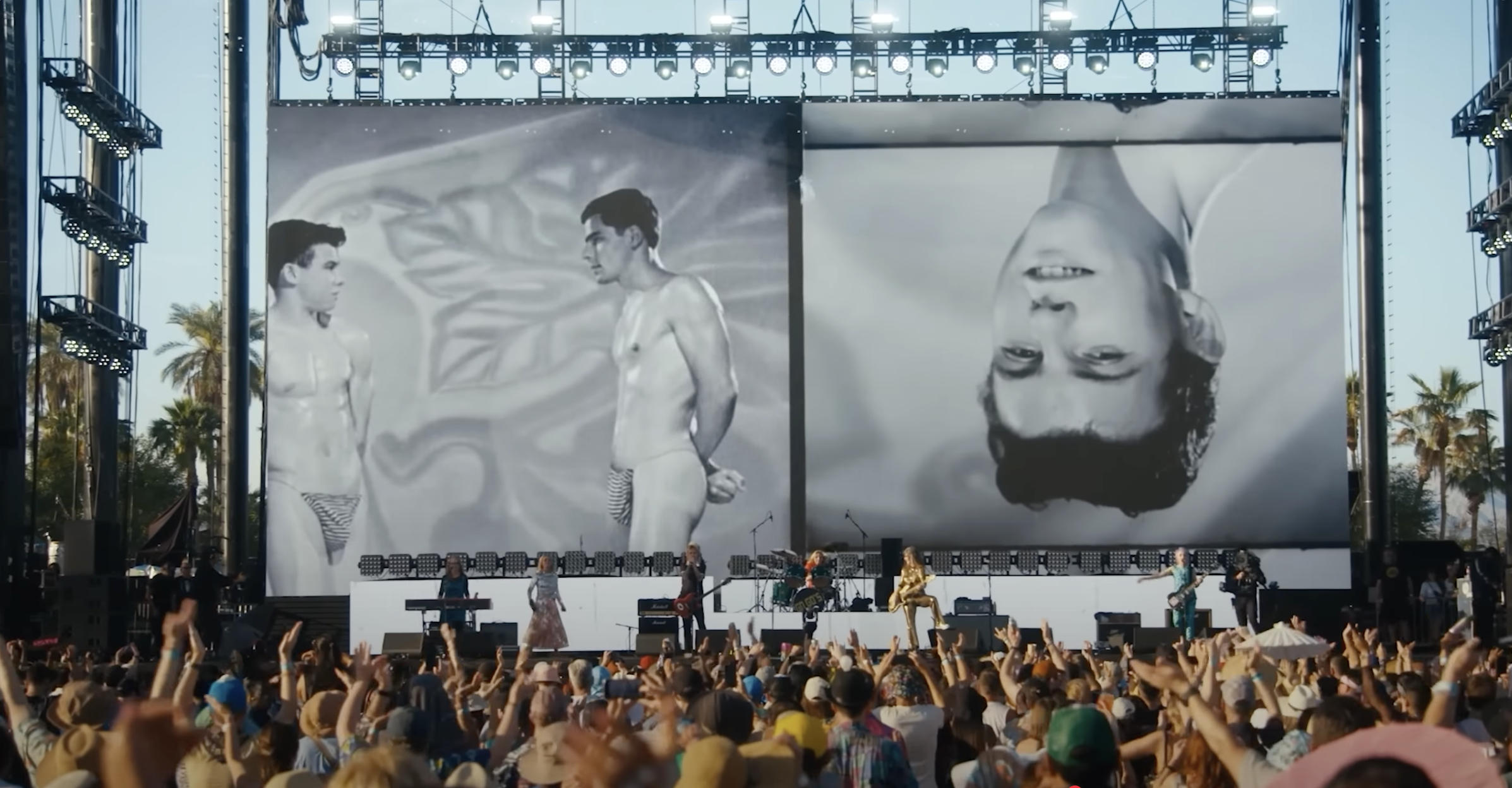

Dive into the mesmerizing fusion of The Go-Go's punk energy and Bob Mizer's vintage underground visuals that made Coachella 2025 unforgettable.

5 min read

Author's note: This is the first in a two-part series on the portrayal of masculinity in the films of director John Waters. Part I covers "Pink...

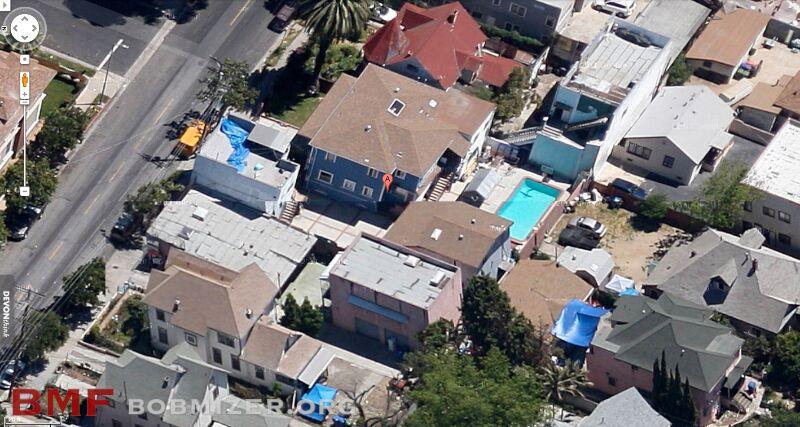

When the neighbors watched Delia Mizer and her precocious 5-year-old son Bob move into the Victorian house at 1834 W. 11th St. in Los Angeles in...