3 min read

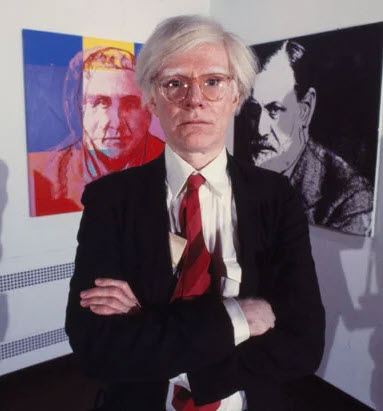

Warhol films celebrated beauty of the mundane

Bob Mizer Foundation : Updated on April 6, 2024

At the same time photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer’s empire expanded and embraced nudity in front of the lens at his L.A. compound, on the other side of the country, pop artist Andy Warhol’s fame also grew.

Next year will mark the 30th anniversary of Warhol’s death. Known for his colorful silk screen works of pop culture figures, iconic American objects and everyday household items alike, fewer people are aware of his sprawling collection of avant garde films, which explored many of the same themes.

The Pittsburgh native was already a well-known name in New York art circles and galleries by the mid-1960s, by which time Warhol had been featured in art exhibits on the East Coast for several years.

“It was around that time that this menagerie of characters began hanging out in Warhol’s studio, which he simply nicknamed ‘The Factory,’” says Dennis Bell, founder and president of the Bob Mizer Foundation. “In fact, a Mizer favorite, Joe Dallesandro, was a regular at the Factory, appearing in several Warhol films. Joe’s work with both Mizer and Warhol catapulted him to stardom on both coasts.”

Other Factory regulars were as diverse as the subjects of Warhol’s art. They included the singer-songwriter Nico, fashion model Edie Sedgwick, and transgender actress Candy Darling. Warhol shot screen tests of the personalities who frequented his studio – actors, artists, junkies, musicians – in various stages of undress. But it was Warhol’s films that documented the mundane and the routine that sparked reactions ranging from fascination to confusion in the art world.

Other Factory regulars were as diverse as the subjects of Warhol’s art. They included the singer-songwriter Nico, fashion model Edie Sedgwick, and transgender actress Candy Darling. Warhol shot screen tests of the personalities who frequented his studio – actors, artists, junkies, musicians – in various stages of undress. But it was Warhol’s films that documented the mundane and the routine that sparked reactions ranging from fascination to confusion in the art world.

There was the movie “Empire” -- Warhol’s filming of the Empire State Building in July 1964 – clocking in at six and a half hours of footage slowed down into eight hours of the building against the New York City skyline. “Empire,” despite its length and lack of any narrative, was added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry 40 years later. One New York Times reviewer likened watching only a few minutes of “Empire” to “viewing just a postage-stamp patch on the Mona Lisa.”

Other films that took unremarkable activities and brought them to life onscreen included 1963’s “Sleep,” which documented the face of a sleeping man for more than five hours of slumber; “Mario Banana 1” (1964), in which model Mario Montez seductively eats a banana; and “Eat” (1964), which featured artist Robert Indiana eating – many believe it was a mushroom – for an entire 45 minutes. Warhol himself appeared in a 1982 Danish film doing nothing but eating a Burger King hamburger

Arguably Warhol’s most well-known experimental film, “Chelsea Girls,” was released in 1966 and shot in New York’s Chelsea Hotel. Starring Nico and Warhol superstar Mario Montez, the movie was presented in a split screen with two reels playing side by side – and sound coming from only one side. Most of the actors simply played themselves, with the dialogue mostly improvised. Warhol collaborated on “Chelsea Girls” with director Paul Morrissey.

One of the most acclaimed of Warhol’s erotic film offerings, “Blow Job,” focuses solely on the face of the uncredited DeVeren Bookwalter.

“The viewer is to assume he is getting a blow job onscreen – from whom, we don’t know – and we only see his face,” Bell notes. “What makes this film so interesting is how this man’s facial expressions change throughout the course of the 35-minute duration of the film. Sometimes he appears bored, sometimes he looks like he’s pondering something.”

“The viewer is to assume he is getting a blow job onscreen – from whom, we don’t know – and we only see his face,” Bell notes. “What makes this film so interesting is how this man’s facial expressions change throughout the course of the 35-minute duration of the film. Sometimes he appears bored, sometimes he looks like he’s pondering something.”

Much like “Blow Job,” Warhol’s other erotic films include only hints and suggestions of sexuality. One prime example can be found in 1968’s “Lonesome Cowboys,” which stars Mizer model Dallesandro, wrestling and frolicking on a ranch with fellow actors Taylor Mead and Eric Emerson. The more blatantly sexual “My Hustler,” which Warhol completed three years earlier, centers on a male prostitute who lives on Fire Island.

Warhol’s career took a hit in 1968, when a deranged fan, radical feminist writer Valerie Solanas, shot Warhol at the Factory after repeatedly asking Warhol to include her in his films and being largely rebuffed. Though Warhol survived, his friends and audience members at the Factory largely disbanded, leaving Warhol to heal. Hauntingly, his art would continue to be influenced by Solanas’ murder attempt for the rest of his life.

The 1960s, as much as they embodied a spirit of experimentation on nearly every front, were a decade in which Warhol’s pop movement thrived and forever revolutionized the art world.

“Warhol’s films ran the gamut of experimentation, giving us a glimpse of beautiful people engaging in boring, everyday actions, as well as frank, unapologetically sexual situations,” Bell says. “And, like Mizer, Warhol mined his talent from the people around him – those who spent time in his living and work spaces became stars, even if it was only for the 15 minutes he so famously predicted.”