Behind the Lens: The Life and Times of Bob Mizer (Part III)

Author’s note: This is the third part of a four-part series designed to introduce the novice to photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer. We will post a...

6 min read

Bob Mizer Foundation : Updated on April 6, 2024

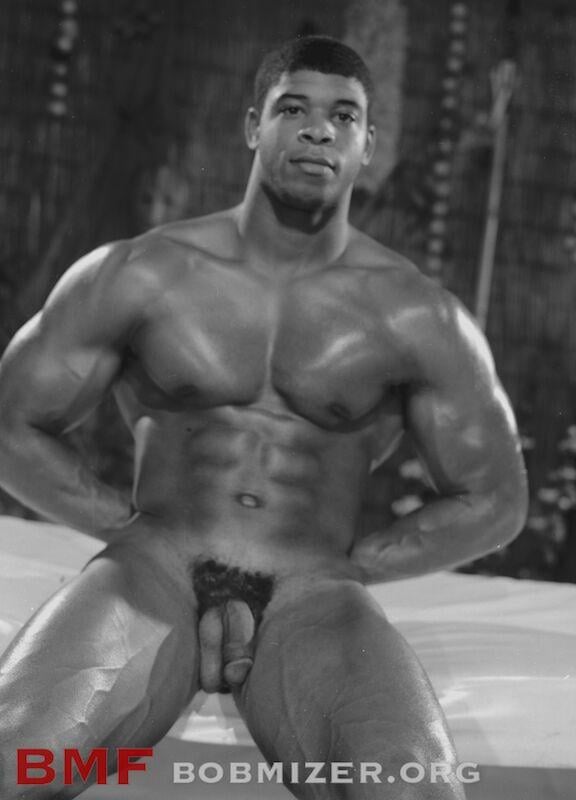

Racial diversity has long been displayed in Bob Mizer’s Physique Pictorial – since the publication’s infancy, in fact. The increasing number of African-American models in the magazine, as well as Mizer’s own notations that accompanied the photos, revealed the changing social landscape of America from the 1950s through the late 1980s.

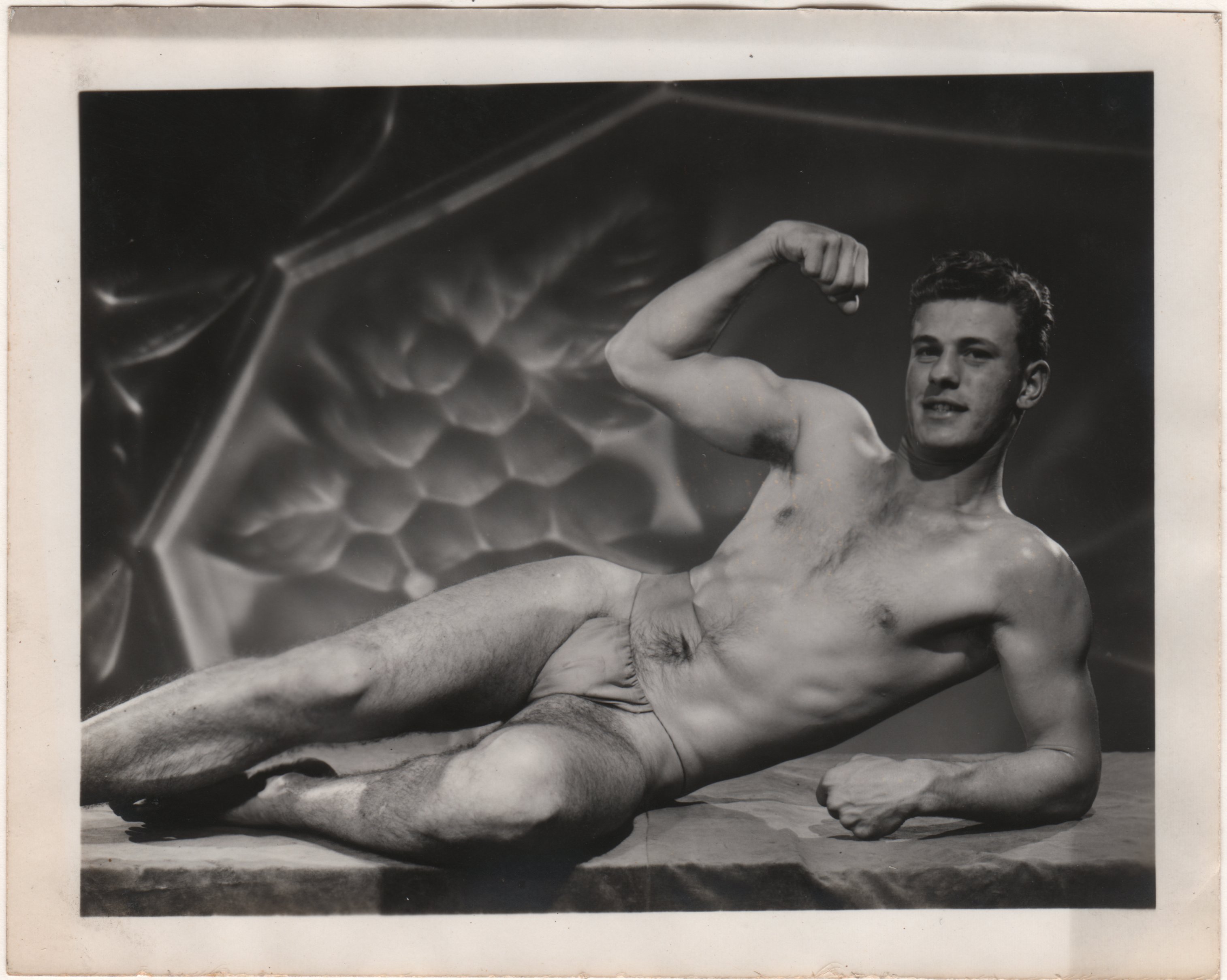

In the years before Physique Pictorial was first published, Mizer searched for his models along crowded California beachfronts and among Hollywood’s packed streets, says Dennis Bell, president of The Bob Mizer Foundation.

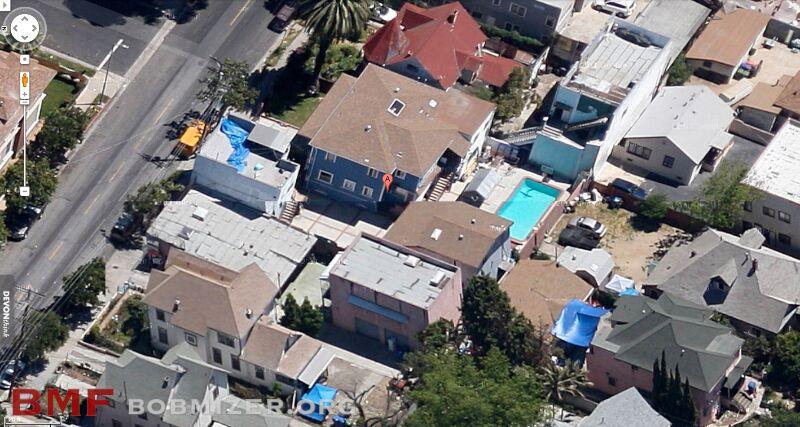

“In the 1940s and 50s, Bob shot models around Santa Monica and Hollywood,” Bell says. “After that, he started shooting closer to home – he wasn’t going to the beaches anymore. He was shooting in his own neighborhood.”

That neighborhood mirrored the almost-exclusively white families winning over the hearts of viewers on television. In Mizer’s own neighborhood, specifically, grand Victorian houses dotted the landscape.

“The houses in Mizer’s neighborhood were built around the turn of the century,” Bell notes. “The houses are old, huge and beautiful. Bob and his mother moved there in the late 1920s. Going into the 1930s and ‘40s, it would have been a classic 'Leave It to Beaver' type of neighborhood – young families, a lot of boarding houses. It was mostly white around that time.”

According to Bell, after Mizer began searching his own stomping grounds for models, the men appearing in his publication became more racially diverse – again, proof positive that the racial demographic of his neighborhood was changing as more blacks and Hispanics moved in.

According to Bell, after Mizer began searching his own stomping grounds for models, the men appearing in his publication became more racially diverse – again, proof positive that the racial demographic of his neighborhood was changing as more blacks and Hispanics moved in.

“In the late ‘50s and 60s, models were being brought to him by various agents,” Bell explains. “That’s when the models started changing.” He says that more Hispanics moved into Mizer’s neighborhood in the 1980s, and that a rise in the number of Hispanic models appearing in Physique Pictorial coincided with this demographic shift.

The first black model to appear in Physique Pictorial was 18-year-old Robert Shealy, who posed for Mizer shortly after being named Mr. California. Mizer noted of Shealy, who appeared in the spring 1953 issue, “Bob’s ambition is to be the first colored man named to win the Mr. America contest.”

Throughout the 1950s, men of color appeared mostly in the periphery of George Quaintance drawings – and if they were at the forefront, they were fighting as gladiators or flanked by tropical foliage in an exotic location. Quaintance, too, praised the beauty of men of all races in his works.

Mizer, meanwhile, donned his white models in ethnic costumes. The most often-used was American Indian garb, such as elaborate feathered headdresses, loin cloths, bows and arrows. The use of the American Indian costume would be a trademark of sorts for Mizer throughout Physique Pictorial's press run. Mizer also used traditional Mexican adornments on white models, including a poncho and sombrero. Nineteen-year-old Alan Colomb, who posed for Mizer in August 1961, even wore a miniature sombrero over his groin area. In that same issue, model Boris Dimitroff dressed as an Arab sultan, complete with hookah, turban and slippers with curled toes.

The arrival of the 1960s saw more African-American men being featured in the pages of Physique Pictorial, along with a few Hispanic and Asian models as well. The first Asian models appeared in the November 1961 issue. Twenty-year-old Katsu Kinoshita appears on a beach in Japan, and Mizer identifies the former high school weightlifter in the caption as “Mr. Gakusei” (or “Mr. Student”) of 1960. On the same page, next to Kinoshita, is 23-year-old Masumi Shigechi, smiling and flexing his muscles on a similar Japanese beach. Two-and-a-half years later, in the May 1964 issue of Physique Pictorial, Mizer dedicated an entire two-page spread to male bodybuilders in Japan, noting in his copy that “there are a few girls interested (in bodybuilding), but for the most part, it is strictly a man’s sport.”

On the second page of the spread, Mizer supplied his own commentary on how traditional standards of beauty can vary from one culture to the next. “And how would you like one of these sickly-looking, faded out, pale-faced Caucasians marrying your pure-bred, dark-skinned beauty?” Mizer asked playfully.

He then extoled the virtue of finding beauty in every race of people. “Almost every race of people considers its own to be the zenith of perfection, sometimes to the unfortunate extreme that it is blinded to the beauty that may exist in others,” Mizer noted. “… Apparently, most races at least secretly feel an admiration for one another. … The Caucasian spends millions on sun-tanning and hair-curling preparations, while his Negro counterpart is buying bleaching cream and hair straighteners. The more we can admire in others, the richer our own lives become.”

He then extoled the virtue of finding beauty in every race of people. “Almost every race of people considers its own to be the zenith of perfection, sometimes to the unfortunate extreme that it is blinded to the beauty that may exist in others,” Mizer noted. “… Apparently, most races at least secretly feel an admiration for one another. … The Caucasian spends millions on sun-tanning and hair-curling preparations, while his Negro counterpart is buying bleaching cream and hair straighteners. The more we can admire in others, the richer our own lives become.”

Despite Mizer's words, Asian and Asian-American models remained largely absent from physique photography in its infancy, according to De Kwok, a volunteer for the Foundation.

"Unfortunately, people of color and in particular Asian models did not have much presence in physique publications during the early period of beefcake photography," Kwok says. "If you were to see a model of color, it was usually African-American models, and even then, their numbers were relatively few. Mizer photographed a few Asian models like Charlie Toka and John Otako for Physique Pictorial. Bruce of L.A. traveled to Hawaii and made photographs of Hawaiian, Filipino and Japanese models."

Mirroring the socio-political climate of the nation at large, men of different races and nationalities continued to become more visible in Physique Pictorial as the decade of the 1960s continued. Nineteen-year-old African-American model Bill Grant, for instance, was featured in a two-page spread in the September 1966 issue, while Hispanic models Jose Ancala and Jose Vela both appeared in September 1967.

Mizer did have a particular affinity for black models, Bell says.

“I was told that Bob had a thing for black models,” he says. “There was a model in 1964 who appeared in a film called ‘Slave Ship’ – Ed Taylor. He was young, about 18, and basically lived with Bob for most of his life. When Bob died, he was still living in Mizer’s compound and working for the Athletic Model Guild, but he was relocated by Mizer's heir.”

Bell speculates that it could be possible that Mizer and Taylor shared a deeper relationship than mere friendship.

“Ed would make Bob meals, and they had dinner together most nights of the week,” Bell says. “I think this guy took care of him. This could mean they were pretty close.”

Beginning in the early 1970s, Physique Pictorial saw a noticeable spike in the number of minorities captured by Mizer’s lens. Niche publications such as magazines and newspapers were being started by publishers nationwide to serve the need of specific ethnic communities in the country’s larger cities. Crowds packed movie theaters for Blaxploitation films. Television shows, for the first time, penned major, starring roles for African-American actors previously relegated to supporting parts. In nearly every discernable way, minorities were being noticed and marketed to in a new way by the nation’s media, and Physique Pictorial was no exception.

A still from Mizer’s film “Love is Color Blind,” referenced in the January 1970 issue, shows a smiling Gene Ray, who is Caucasian, with his arm around African-American model Jim Davis, also grinning. “After some anxious moments during which it seems their friendship has ruptured beyond repair,” reads the description, “Jim Davis and Gene Ray resolve all their differences.”

A still from Mizer’s film “Love is Color Blind,” referenced in the January 1970 issue, shows a smiling Gene Ray, who is Caucasian, with his arm around African-American model Jim Davis, also grinning. “After some anxious moments during which it seems their friendship has ruptured beyond repair,” reads the description, “Jim Davis and Gene Ray resolve all their differences.”

In the January 1974 edition, Mizer makes specific mention of films and images of mixed-race pairs of models, which likely means he had received requests for such material from numerous readers. Next to a nude portrait of African-American model Russell Mathews, lists a few “Negroe-Caucasian” films and then notes, “A number of other Neg.-Cauc. films have been made but not released in 8mm, but can be ordered.” Mizer also lists films featuring solo black models, as well as dual black models. Mizer advertises still images of black models on the following page, next to a portrait of African-American model Kenneth Calvin Collins, dressed in a cowboy costume.

The December 1974 issue features language more playful and peppered with slang in describing model Johnny Johnson, posing in a construction helmet and tool belt. Johnson “says he would prefer to be a whorehouseman and tries to keep a string of girls busy for him. Unhappily, his ‘honky’ girlfriend ‘ratted’ on him, and he is no longer available for posing,” according to Mizer’s photo caption.

The December 1974 issue features language more playful and peppered with slang in describing model Johnny Johnson, posing in a construction helmet and tool belt. Johnson “says he would prefer to be a whorehouseman and tries to keep a string of girls busy for him. Unhappily, his ‘honky’ girlfriend ‘ratted’ on him, and he is no longer available for posing,” according to Mizer’s photo caption.

Throughout the mid-1970s, Mizer added Puerto Rican, Jamaican and Cherokee Indian models to his menagerie. His penchant for ethnic costumes continued well into the 1980s, when African-American models were shown airborne in a harness or wrestling one another and their white counterparts in front of the colorful backdrops adorning Mizer’s studio. Black models from Mizer’s work from the 1980s are featured prominently throughout Dian Hanson’s “The Big Penis Book,” as well as the 2009 coffee table book, “Bob’s World.”

The last African-American model to receive his own page in Physique Pictorial was Dennis Johnson in the September 1990 issue. Noting that Johnson had posed for and appeared in films for AMG since 1979, Mizer ended his comments on Johnson with yet another promotion of his works featuring black models, showing that demand for them was still high among his readership.

The last African-American model to receive his own page in Physique Pictorial was Dennis Johnson in the September 1990 issue. Noting that Johnson had posed for and appeared in films for AMG since 1979, Mizer ended his comments on Johnson with yet another promotion of his works featuring black models, showing that demand for them was still high among his readership.

“I think that even if Bob wasn’t solely into certain types of guys himself, he did indeed like black guys and he did like young guys – that would be his type,” Bell says. “I think he was shooting mostly for his customers. He was very aware of the fact that everybody has a type, and he was shooting those types. He shot not for himself, but for his customers.”

Although Mizer may have been limited in the media through which to publish and share images of models of color, the advent of the Internet and social media will inevitably make these men more visible, Kwok notes -- but the progress is slow. He cites artists Danny Dan (www.dannydanphoto.com) and Norm Yip of Beaux magazine as two contemporary artists whose works place Asian men "front and center."

"The Internet and the rise of self-published photobooks and zines have been a boon for people to photograph and publish physique imagery," he says. "I think the future of Asian physique (photography) will only continue to grow."

Author’s note: This is the third part of a four-part series designed to introduce the novice to photographer and filmmaker Bob Mizer. We will post a...

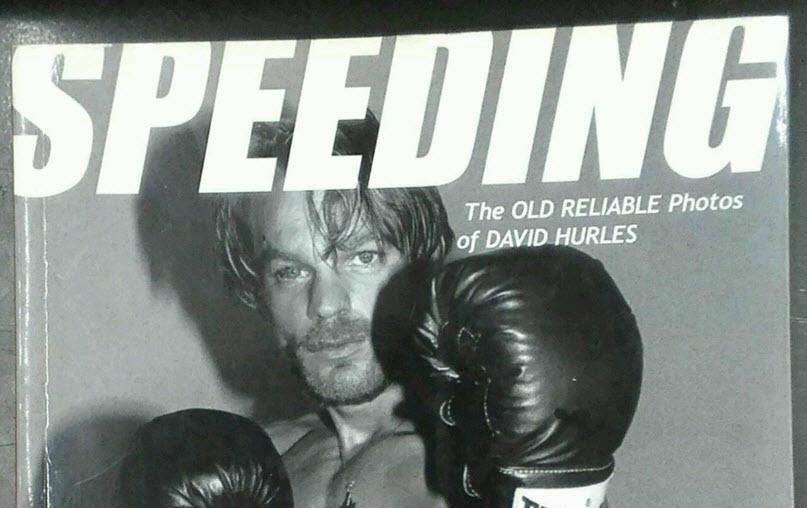

Raging hard-ons, sketchy prison tattoos, and junkies, junkies, junkies – they have all been represented in contemporary art, but never like this....

When the neighbors watched Delia Mizer and her precocious 5-year-old son Bob move into the Victorian house at 1834 W. 11th St. in Los Angeles in...

In the 1940s and 1950s, there existed a group of men who were both excited and fearful when they made the trek to the mailbox every day.